23 Oct Weather Channel Bets on Immersive Reality with Simulations of Local Weather Forecasts

The network unveils Virtual View for 50 cities across the country

By Matthew Cappucci

It made for fast-paced, dramatic and visceral television — and yet it was merely a simulation. From the digitally superimposed rubble of mangled cars, shredded trees and tattered remnants of homes and businesses, Cantore explained the importance of heeding lifesaving warnings issued before the onset of such violent weather.

And in the blink of an eye, he was back in the studio — flanked by a news desk, paneled monitors and a decorative vase.

The thrilling presentation was lauded by media critics, many heralding it as the future of television weather storytelling. The network even took home an Emmy for best medical or science reporting at the 40th annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards in 2019.

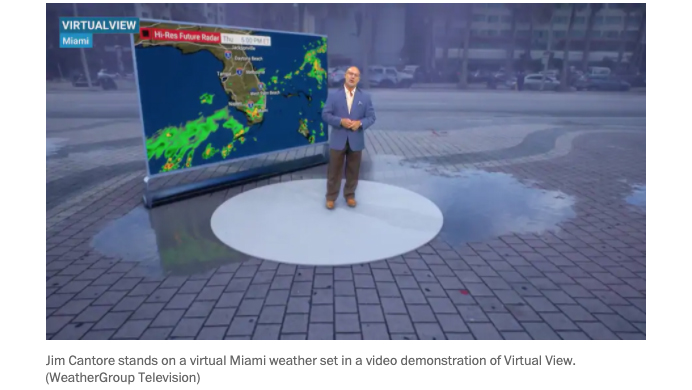

Since then, the Weather Channel has rolled out a dozen or more immersive mixed reality, or IMR, explainers, digitally transporting their meteorologists to the scene of fire tornadoes, hurricane-driven storm surges and ferocious thunderstorms. Now, the station’s IMR endeavors are expanding into everyday forecasting through an initiative called Virtual View.

The network aims to introduce live, real-time immersive mixed reality storytelling for 50 cities across the United States. Gone are the days of standing in front of stationary maps and graphics adorned with icons. Now, network executives hope to transport on-camera talent — and viewers — into the weather forecast itself.

At a time when many viewers are cutting the cable cord and relying on phone apps and websites for weather forecasts, the station is betting that unique experiences like IMR can hold on to a TV audience.

“This is transforming our capabilities of weather presentation,” Nora Zimmett, chief content officer and executive vice president at the Weather Channel, said during a conference call. “To be able to take people into these areas in the future without them ever leaving their living room is a valuable tool.”

Mike Chesterfield, the network’s director of weather presentation, explained how powerful of a messaging tool IMR has become.

“Ahead of Hurricane Florence, we were able to show … what surge would look like,” Chesterfield said. The network had created an artificial version of Newport, N.C., and digitally flooded it with a 10-foot wall of water.

“As a meteorologist, that was the first time I saw the [audience] reaction we were looking for,” Chesterfield said. “It got the audience to react in a way that was surprising and also a way we were going after.”

The network’s hope is to be able to show viewers the weather they may face before it occurs — not just from a weather model but, rather, by simulating the actual environment.

“This is literally taking the talent to stand in front of locations and actually watch what the weather will be before it actually happens,” Chesterfield said.

That means you won’t see IMR segments limited to life-threatening storm surge or destructive tornado events. It will become a staple of day-to-day weathercasts, depicting a chance of gusty thunderstorms or a sunny, breezy afternoon.

“One of the best things about Virtual View is [being able to articulate] what the weather is going to be like,” said Weather Channel meteorologist Stephanie Abrams. “When we say there is a huge thunderstorm and it’s going to dump this much rain, we’re actually going to be able to show this to the viewers.”

Bob Ryan, former chief meteorologist at WJLA-TV and WRC-TV in Washington, said he’s eager to see what the technology could offer but worries that overuse could diminish its effectiveness.

“I think in major weather events where you want to get the proper decision made by the user, it could really be a useful tool,” Ryan said. “I wonder if using it every day for things like sunny weather [could get old]. Use it selectively, I guess.”

Ryan also said communicating uncertainty in a forecast may be difficult with the new tool.

“If you’re showing a visual forecast and it’s a 50 percent chance of severe weather, how do you graphically show that?” Ryan said. “Or if it’s going to snow and [it’s between] two inches and 10 inches?”

To create these virtual landscapes, engineers from the Weather Channel traveled to each of the 50 cities where they chose to capture imagery. Warren Drones, who led the graphics team tasked with constructing the virtual environments, said the photos they took had to meet particular standards.

“We have our own in-house team that manipulates the photos to make [them] look authentic,” Drones said. “We want to make sure it … doesn’t look like someone’s photo of New York; it looks like New York.”

Ryan said that the use of scenery with recognizable elements goes a long way in helping viewers to connect with the conditions heading their way. Some viewers have trouble reading maps but know geographic markers and landmarks, Ryan said.

To pull off the visuals, on-camera presenters deliver their forecasts in an enormous green screen studio, shaped and painted in a specific manner to align with the corresponding digital space.

“We had to consider everything,” Chesterfield said. “The shape of the green screen space, the lighting that is used, the shade of the green … [it’s] all designed with the goal of producing the best keying possible,” he said, using an industry shorthand for chroma keying, the process the makes a green screen work.

Marks on the floor guide on-camera meteorologists as they interact with the virtual set.

“When it comes to training with the whole system, fortunately I played Mario Brothers and other video games as a kid, and that helped hand-eye coordination,” Abrams said with a laugh. “Sometimes you see the floor director waving you up saying, ‘You’re going to run into the graphic.’ … There are four of five little marks.”

The product is so realistic that there’s little to clue viewers in to the fact that it’s not real. But Zimmett said this will never replace being in the field. That’s central to the Weather Channel’s mission, she said.

“I am a big believer of sending people into the field,” Zimmett said. “Not for the theater of it but to show why we … tell you to leave when evacuations are recommended. To get that boots-on-the-ground experience … is very valuable.”

Abrams, who was in Lake Charles, La., during Hurricane Delta, told of delivering live reports in front of a building damaged in the wind. The building’s owner, who had evacuated, was apparently watching her coverage at the time.

“I would say within 20 or 30 minutes, he had a good five friends out there with trucks and boards, and they put it all back together,” Abrams said. “That’s just something you can’t get unless you were in the field. I think being there physically with them before, during and after makes a huge difference for our viewers.”

Read the full article here.

Read the full article here.