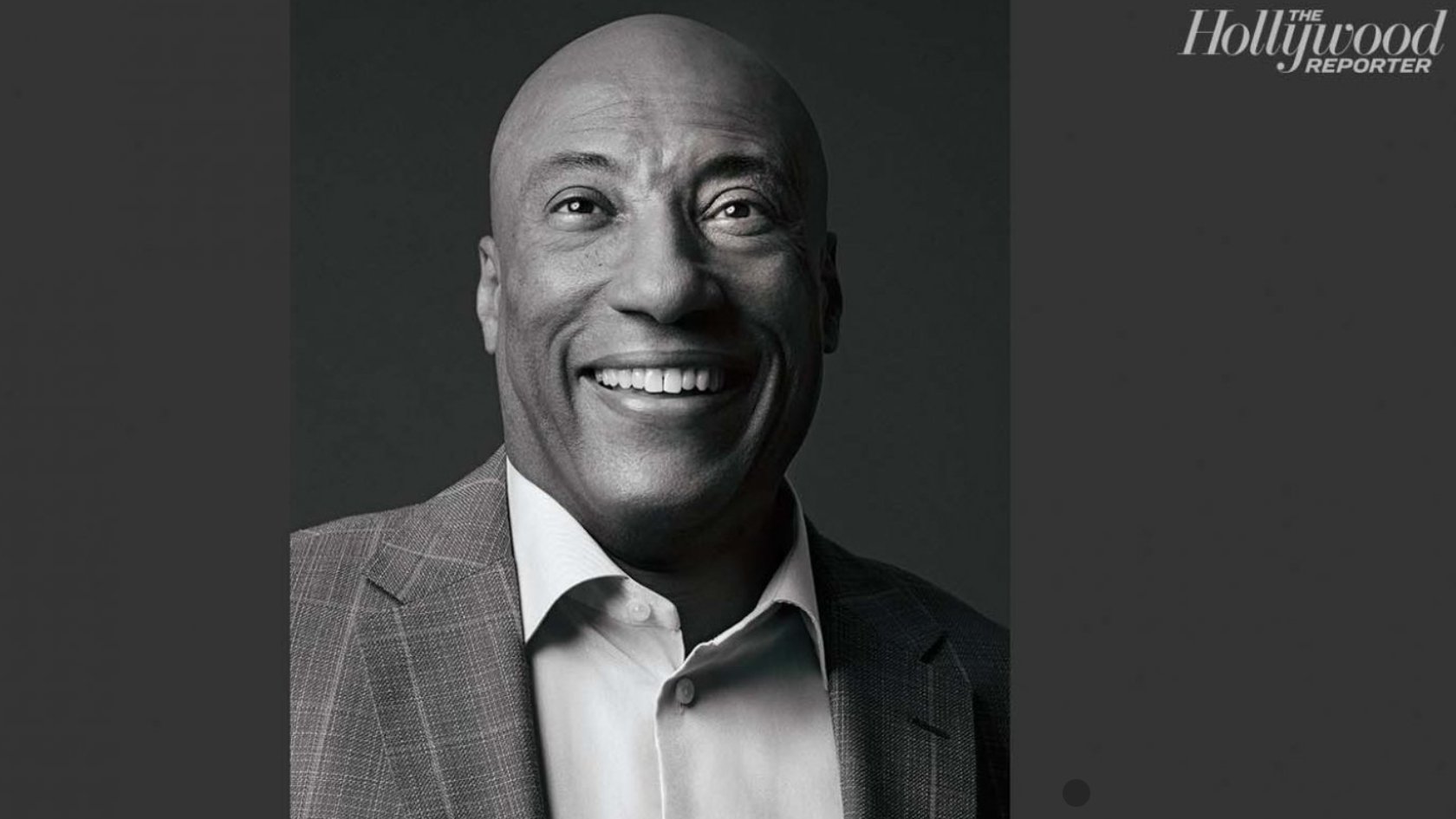

09 Jul Byron Allen on His Plans for Media Domination: “What You See Today Will Be 10,000 Times Bigger”

By Seth Abramovitch

The comic turned mogul has played the long game since he was a kid, acquiring assets like The Weather Channel and taking a racial equality dispute with Comcast all the way to the Supreme Court: “I’d love to own CNN. … And I will.”

On June 14, as much of the country poured out of self-quarantine and into the streets in support of Black Lives Matter, Byron Allen let his feelings be known in characteristic fashion — which is to say from the rooftops. The stand-up comic turned media mogul spent $1 million to buy two pages in eight major papers — including The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post — to run an op-ed he’d tapped out on his laptop, titled, “Black America Speaks. America Should Listen.”

“I knew white media wasn’t going to publish it,” Allen, 59, asserts of the essay, which traces childhood memories of the National Guard invading his Detroit neighborhood after unrest following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, then lays out a nine-step plan to eradicate racial inequality, including education reform and reparations. “Because that’s talking about how you really fix it. White America doesn’t want to fix this. White America is not interested in giving up any of their pie.”

Allen would know. As one of the few African Americans to own and run a major media company — and his Entertainment Studios is major, producing more than 60 syndicated TV shows; owning The Weather Channel and seven more 24-hour cable networks; acquiring and distributing features like 47 Meters Down and Hostiles; snapping up TheGrio, a Black-interests website; and, most recently, purchasing 15 local TV stations, representing all the Big Four broadcast networks — he has witnessed firsthand the roadblocks to Black entrepreneurs wanting a piece of the big-media game.

“African Americans don’t have access to capital,” Allen says. “It’s amazing that for the first 15 to 20 years of my company, I couldn’t get a single bank loan.” It was that early resistance, however, that fired his ambitions, turning what started in 1993 as a one-man operation in his dining room (his mom fielded calls as his “executive assistant”) into a muscular media company that Allen values in the low-10 figures. “If someone offered me $5 billion for the company,” he says, “I would not accept it.”

Along the way, he’s had a habit of ruffling feathers and commanding headlines — such as with the $30 billion racial discrimination lawsuits he filed against Comcast and Time Warner Cable (now Charter) in 2015 for refusing to carry his channels, which wound itself all the way up to the Supreme Court. Or calling President Barack Obama “a white president in blackface” to TMZ, in response to Obama’s calling Baltimore looters “thugs” after the 2015 death of Freddie Gray, a young Black man who suffered fatal injuries while in policy custody.

But there are no regrets. Today, in the shadow of George Floyd’s killing — what he likens to a “horizontal lynching” — Allen feels entirely vindicated. “A lot of Black people were upset about [the Obama insult], but I’m glad I said it. And now, five years later, people finally understand what I’m saying.” The loans, meanwhile — like the $300 million he raised in 2018 to buy The Weather Channel — come much easier these days. And if his old-school bluster makes him sound like a mogul with something to prove, that’s perfectly fine with him.

“For me, it’s important to own something — especially in America, as an African American,” he says. “As far as I’m concerned, I can’t own enough. It’s not possible. I haven’t even begun.”

***

As media mogul origin stories go, Allen’s is a good one. The summer after the unrest in Detroit in April ’68, his mother, Carolyn — who had him at 17 — packed up the car and moved her 7-year-old son to L.A. (Raised an only child, Allen has a half-brother on his father’s side; he remained close with his dad, who stayed in Detroit and died in 2019.) Carolyn enrolled in UCLA’s film department in 1971 and talked her way into an internship at NBC — she actually suggested the program and was its first recruit — and was eventually promoted to publicist. Byron’s day care routine involved hanging out at the Burbank studios, where he’d observe the biggest comedy stars of the day at work — giants like Redd Foxx, Freddie Prinze and, most intently, Tonight Show host Johnny Carson, who’d greet him in the corridors with a bright “Hello, Byron! How are you, young man?”

By his early teens, Allen wanted to give comedy a try. He heard the place to be was The Comedy Store, so he would loiter on the Sunset Strip every night, pages of jokes tucked in his pocket, hoping to win a spot on the open-mic stage. His persistence paid off: Owner Mitzi Shore eventually let him inside to perform, so long as he promised not to drink. (To this day, he has never touched alcohol, drugs or cigarettes. “I don’t even golf,” Allen says.) The jokes were apparently good enough to get him scouted by Jimmie “J.J.” Walker, the breakout star of CBS’ Good Times. So at just 14, Allen would be dropped off by his mom at Walker’s house, where he sat alongside two promising young comics pitching jokes at $25 a pop. Their names were Jay Leno and David Letterman.

“He always pitched well,” Leno recalls. “It was never like, ‘Oh God — would this kid just shut up?’ Our points of reference were so different — I mean, he was literally a teenager in school and we were adults out of college. But he always brought an interesting sensibility to it. He was good at finding the right word.”

By 18, Allen landed a life-changing spot on The Tonight Show, the youngest comic ever to take that stage. Delivered in a tweed blazer, his act was mostly soft-edged observational humor about his parents, with occasional stabs at edgier material. (One joke involving a Native American war cry would not fly today.) That one appearance — bolstered by Carson’s affection for Allen — led to a number of TV offers. He chose NBC’s Real People, an early reality show, which made Allen famous as he crossed the country profiling quirky Americans.

When Eddie Murphy made his first trip out to L.A. in 1980 — he was in his first season of Saturday Night Live and was booked to appear on The Tonight Show — he was determined to meet Allen. “Byron was one of my first inspirations,” Murphy says. “When I was a kid, Byron was on Real People. Then he’s writing for TV shows and shit like that. I knew about him when I was starting out — that there was this guy who was about the same age as me out there making it happen.”

Allen appeared on Real People from 1979 to 1984, but when contract negotiations went sour — a younger, cuter teen was brought in as a co-host — Allen decided to take matters into his own hands. (“It’s business show,” goes one of his favorite mantras. “Not show business.”) He refinanced his home in 1992 to produce his own celebrity talk show that taped seven times a week. “I had to pay the cameraman, the sound man, the tape stock,” he recalls. “It was really tough for about five years.”

Allen sold the show by calling hundreds of network affiliates around the country. He’d often call the same station dozens of times before landing a yes. (He got station managers to pick up by asking for the newsroom and having them transfer him.) After a few years of producing the show and living hand-to-mouth, he’d compiled enough footage to cut together an hourlong special of interviews with celebrity athletes like Michael Jordan and Oscar De La Hoya. It cost him $20,000 to produce and earned him $1 million in commercial sales. “Back then it was ‘1-800 SPRAY-ON HAIR,’ ‘1-800 24-HOUR ABS,’ ” he says of his early advertisers. “That special got me off my dining room table and allowed me to open my offices in Century City and start hiring.”

It was a lightbulb moment: Content would forever be king, and whoever has the most, wins. Today, Allen produces more than 60 shows — a mix of Allen-hosted talkers, celebrity game shows like Funny You Should Ask and courtroom shows like The Verdict With Judge Hatchett — most of them done quickly and on the cheap. (Allen likes to tell the story about how he paid Paramount Studios $1 to take a discarded courtroom set off their hands.) “He doesn’t take no for an answer,” says buyer Peter Dunn, president of CBS Television Group. “He’s very aggressive, very confident and thinks big. That’s great for a businessperson.”

Twelve years ago, Allen turned his attention to owning cable channels. He did so in an unusual way: by snapping up every desirable dot-TV domain name. “I own all the premium dot-TVs,” he says. “Comedy.TV, Cars.TV, Pets.TV. I have dot-TVs I haven’t even turned on yet: Sports.TV, Kids.TV.” Go to those URLs now and you won’t find much — the content on those Allen-owned HD channels resides on cable and satellite TV. Verizon was an early buyer when it started its FiOS fiber-optic network in 2009, launching six of his channels in a single day. But other cable giants held off — and that rubbed Allen the wrong way.

In December 2014, he embarked upon what would become a five-year legal odyssey that would initially draw snickers from the industry — but Allen may have the last laugh. “I’m not a litigious person,” he says. “I have not filed that many lawsuits — I think I have filed four in my life, but they’ve been big and epic.” His case hinged on the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the country’s first civil rights law, enacted to ensure that newly freed slaves had a pathway to economic inclusion. Former President Bill Clinton was so impressed with the tactic, he personally congratulated Allen on exploiting a largely untested law.

AT&T settled, agreeing to carry channels like Comedy.TV and JusticeCentral.TV on DirecTV and U-verse. But Comcast and Charter put up a fight, waving off his “frivolous” $20 billion and $10 billion lawsuits against them, respectively, and firing back that his content did not show sufficient “customer demand to merit distribution.” The suit initially named the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Network, the National Urban League and the NAACP, claiming they unfairly brokered deals with Comcast on behalf of African American-owned media, which the parties denied.

Allen later dropped those African American leaders from the suit, but defends his original impulse to include them. “I said to a white executive, ‘Who is the white guy who speaks for all white people — and why do you think there’s a Black guy that speaks for all Black people? The very idea that you think somebody speaks for me is a racist idea,’ ” he says. That tendency to run counter to the flock has earned him a fair number of detractors. “There are a lot of Black people mad at me,” he concedes.

To that, Allen points to his track record. “My lawsuits were a rallying call for Black America to say, ‘If he can do this in his industry, we can do this in ours,’ ” he says. “And no one has more positive images of Black and brown people on the air. I put five judges [of color] on — Judge Ross, Mablean, Judge Hatchett, Judge Karen and Judge Cristina Perez.”

In November, arguments in the Comcast suit were heard by the Supreme Court. Allen brought in the dean of Berkeley Law, Erwin Chemerinsky, to plead his case. (“He has written 11 books on this and is the best of the best,” Allen says.) Nevertheless, the court ruled nine to zero against him in March. In its opinion, the court concluded that race needed to be the deciding factor in Comcast’s decision not to carry Allen’s channels. It sent the case back to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

On June 11 — three days before his op-ed ran — Allen and Comcast issued a vague joint press release, stating that the cable company will continue to broadcast The Weather Channel, plus “additional” Allen-owned content. The Charter case, meanwhile, is still on track for a courtroom showdown. Allen relishes the opportunity. “I happen to be extremely fortunate in a situation where I can spend tens of millions on litigation over a five-year period and be very comfortable,” he says.

***

Allen loves to talk and glides with ease from Big Topic to Big Topic — in the span of five minutes he can weigh in on everything from global warming to competing with China. He’s a charismatic storyteller and fierce debater, pulling stats out of thin air to bolster his points. (Not all of them add up. “China has over 200 million kids in college mastering things like STEM,” he says. The actual number is closer to 40 million.) If it can start to sound like a stump speech, rest assured, there will be no “vote Allen” robocalls any time soon. “I don’t want to be a politician,” he says. “I don’t even like politicians.”

Still, the self-described “staunch Democrat” is a fixture at the kinds of power fundraisers regularly thrown by his friend Jeffrey Katzenberg, founder of Quibi. It was at one of those events shortly after Obama won his second term that Allen took the president to task. “I asked Obama, ‘Why don’t you audit the banks and see if they lend any money to Black people, because they are not,’ ” he says. “I asked him in front of about 50 people at [L.A. restaurant] Fig & Olive. Judd Apatow came up to me and said, ‘Oh my God — you have the biggest balls in the world.’ ” Fired up, Allen delivered his “white president in blackface” tirade on TMZ soon after. Obama assured him that he heard his criticism and would reach out. “But he never did,” Allen says, “like a typical politician.”

But that was then. Allen — who raises three children, ages 7 through 11, with wife Jennifer Lucas, a TV producer — is now more determined than ever to get “category-five disaster” President Donald Trump out of office, and has thrown his full support behind Obama’s former lieutenant, Joe Biden. “Katzenberg had a terrific [fundraiser] at his office before [Biden] even announced,” Allen recalls. “It was the heads of pretty much all the studios saying, ‘Hey, just want you to know: If you decide to run, we’re here for you.’ I was like, ‘Dude, whatever you need — we got you, you know, we got you.’ ”

Says Katzenberg of Allen, “You can’t succeed as a businessman without being tough. You’ve got to have bare knuckles, and he’s a fighter. That’s why he wins. But there’s this other side to him that is someone who has a very big heart and is generous. He’s had a phenomenal impact as a businessman, but I’m almost more impressed by his philanthropy. He sets a high bar.”

Those philanthropic efforts include a splashy Oscars-night fundraiser, now in its fifth year, where Katy Perry and Maroon 5 have performed. The gala, which costs Allen $1 million to produce, benefits Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where as a child he was treated for a severe infection that nearly required a leg amputation. More recently, he threw together a virtual comedy benefit for the food-bank network Feeding America. The special, which featured longtime friends like Murphy, Whoopi Goldberg and Tiffany Haddish, raised $2 million on its May 10 airing on NBC.

“You know how you can sum up Byron is his chess game,” Murphy explains. “Byron played a lot of chess back in the early days. There was a group of people in town, like Berry Gordy and Jim Brown, who would fly in good players. I played Byron a lot. I’m a much better chess player than Byron. Like, nobody beats me. If I had played Byron on the clock, I would have killed Byron. But we didn’t play on the clock — we just played. And that’s Byron’s game. He’s super patient. He takes a long time between every move. He does it until you get frustrated — and then you do something stupid, and then all he needs is a little tiny crack. Just a pawn, any type of advantage, and he had you. That is Byron in a nutshell.”

That patience will come in handy as he enters the next phase of growth for Entertainment Studios Inc., where, in true Allen style, nothing short of total global domination is the plan. “I’m close to the same age when Rupert Murdoch came here to America,” he says. “He was in his 50s. I’m 59. What you see today will be 10,000 times bigger.” Press him on what would make the ultimate jewel in his crown and, without hesitation, he replies, “I’d love to own CNN. But I have to buy AT&T to do that. And I will. Believe me, I think about it every day.”

This story first appeared in the July 8 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

Read the full article here.

Read the full article here.